Perdix hardly cuts a common figure in our contemporary awareness of classical mythology. You may not have ever noticed him. Perdix flies too low for notice and only rarely squawks from the fringes. A couple of well-known Renaissance paintings adapt the Perdix myth. These adaptations have allowed Perdix to escape like an upland game bird into the dense underbrush of classical mythological adaptations.

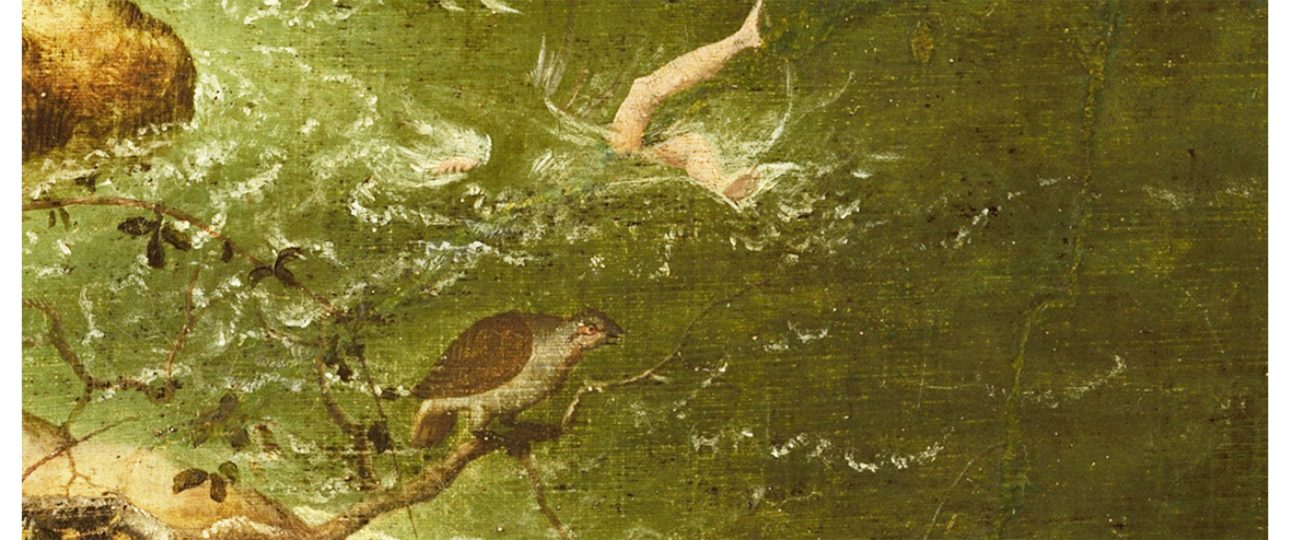

Pieter Brueghel the Elder’s iconic “Landscape with The Fall of Icarus” perches the chortling perdix bird on a limb right beside Icarus’ fatal crash into the sea. Brueghel’s painting overtly reverses the human observation that plays prominently in Ovid’s narrative: nobody in Bruegel’s painting seems to notice Icarus’ mortality. Ironically, Perdix does. And Bruegel’s chattering bird notes full well the demise of a rival. Brueghel places Perdix as the closest living thing to fallen Icarus. And the bird responds open-mouthed to the boy’s loss.

Though in classical versions Perdix played a critical role in Daedalus’ exile to the Minoan court on Crete, the young man’s obscurity never rises to the notoriety of Icarus’ hybristic flight nor of Daedalus’ ingenuity. Yet, back in Athens Perdix had been poised to become the more clever engineer, even better than his uncle Daedalus, to whom Perdix had been apprenticed. The precocious youngster Perdix — in some ancient authors he’s known as Kalos or Talos — quickly outshone his clever uncle. He invented the compass, the potter’s wheel, and the saw. This last invention sprang from Perdix’ fertile observation of a fish skeleton. Perdix died — or, better, was metamorphosed — plummeting headlong (praeceps lapsus; Ov. Met. 8.251 — pushed from the Athenian Acropolis during his apprenticeship to Daedalus. When Perdix fell, Daedalus’ known jealousy for the young ward’s ingenuity brought from the Areopagus suspicion of foul play (propter artificii invidiam; Hygin. Fab. 39), a capital charge for which Daedalus was banished. No witness observed that in his last moment Perdix had been transformed — either by Athena’s intervention or by the clever boy himself (!)[2] — into the famously low-flying bird, the partridge.

Ovid, whose narrative Brueghel adapts in his picture, caps his timeless episode of Icarus and Daedalus’ tragic flight (Metamorphoses 8.183-235) telling Partridge’s schadenfroh delight at Daedalus’ abject grief over fallen Icarus:

Hunc [i.e. Daedalum] miseri tumulo ponentem corpora nati

garrula limoso prospexit ab elice perdix

et plausit pennis testataque gaudia cantu est:

unica tunc volucris nec visa prioribus annis

factaque nuper avis, longum tibi, Daedale, crimen. — Met. 8.236-43A chatterbox partridge watched from a marshy furrow as Daedalus laid

his son’s pitiable body in a grave. It applauded with wings, manifesting

its exultation in the squawking. The then-novel fowl, never seen in foregone days,

recently created, chirps at you, Daedalus, your everlasting crime. — Trans. RTM

Ovid wants his reader to notice Partridge in this closure to the Daedalus episode. For the narrator prolongs the rustling bird’s incriminating taunt in the triplicate emphasis on the Partridge’s novelty. Though Daedalus had contrived a way for humans to imitate birds, Perdix’ metamorphosis, which had occurred years prior, is a full transformation from human to bird. Ovid continues, observing that Minerva’s intervention had protected the boy from headlong death, transformed him mid-air into a bird and clothed him in feathers while also infusing his native cleverness into fleetness of wing and of foot. The transformed Perdix ironically contrasts his cousin’s impetuousness by never flying high to lofty nests in treetops but ever flying close to the ground where, having learned an important lesson, the partridge lays its eggs in hedges, antiquique memor metuit sublimia casus: mindful of that old fall, Perdix still eschews heights … and he still has a lot to say.

Bruegel’s “Icarus” uses the Perdix myth to enrich the Icarus narrative. The homage to Ovid attests to the persistence of the Metamorphoses‘ influence.

Other treatments of the Perdix myth include Apollodorus, Library 3.15.8, Hyginus Fabulae 274, Pliny Historia Naturalis 7.57, references offered by Robert Graves Greek Myths 92.b.

No article in OGCMA treats Perdix separately, though he is mentioned s.v. “Icarus and Daedalus”.

— RTM

[2] Michael Simpson (1976) Gods and Heroes of the Greeks: the Library of Apollodorus (Amherst: UnivMassachusetts Press), 218 argues that Ovid’s text suggests here that ‘Perdix himself invented his transformation while falling.’

[3] Robert Graves (1955) The Greek Myths (Penguin) 92b, sees Perdix’ fall from the Acropolis as Daedalus’ murder and cover-up

that Perdix had offended Daedalus by having incestuous relations with Polycaste — Perdix’ mother and Daedalus’ sister.