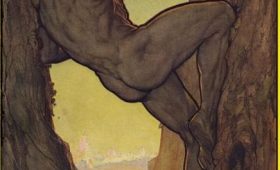

The British National Gallery’s painting of the month for October 2021 is an old favorite of mine, “Minerva Protects Pax from Mars (or, Peace and War)” (1629-1630).

Having spent much of my weekend with my beautiful little granddaughters, contemplating the painting this morning takes me by storm. There is plenty in Rubens’ big canvas to distract the eye. The figure of Pax (Peace) suckles (half-)man and beast with such abundance that here mere proximity nourishes them. The swirling maenads add the musical accompaniment. But the effort being taken to hurry the children into Pax’ presence is touching. The frightened gaze of the little blonde girl, looking outside the frame to connect with me (the viewer), and her sister’s busied concern make me think of two children who mean everything to me.

In an imperfect world where violence might crush tender innocence, Rubens provides a powerful allegory for the strength of divine protection. Cultivate Minerva and your nation will thrive.The peace-fostering goddess Minerva energetically — even with her bare hands! — drives back the war-mongering Mars and his attendant Bellona.

A few years ago I wrote this (AresAthena1.0005_Rubens):

This gift to Charles I was painted while Rubens was in England as an envoy from Philip IV of Spain and clearly articulates the painter’s attitude toward British-Spanish diplomacy. (Cf. Baker & Henry). Rubens himself said his successful diplomacy was “the connecting knot in the chain of all the confederations of Europe.” (Schama, 208)

Homer calls both Ares and Athena “warlike” (πολεμηίος). But, clearly their approach to warfare is distinctly opposite: Athena is defensive, strategic warfare and Ares represents the bloodthirsty madness of violent war. Athena, as champion of civilization, employs wisdom to defend society from the ravages of war.

“Peace is not merely the absence of war, but also the source of abundance.” (NG site) Rubens adds considerable detail to an allegorical scene stylized by Tintoretto about 50 years earlier. Rubens also repeated the trope on the ceiling of Banqueting House about three years later and then less optimistically in “The Horrors of War”in Palazzo Pitti Florence (cf. pensées in NG, the Louvre and elsewhere). Within this narrative set, Minerva interposes herself vigorously for the protection of civilization against the ravages of marauding Mars.

C. Baker and T. Henry, The National Gallery: complete illustrated guide (London ), 595 offer substantial bibliographic leads; and now S. Schama New Yorker 28 Apr 2007, 207 – 20.