Linda Hutcheon’s Theory of Adaptation holds a canonical place on my bookshelf and in my heart. The book’s sanity cuts through problems of theorizing adaption. Hutcheon’s approach is unencumbered by jargon and murk. Since its publication in 2006 and revision in 2013 — 2nd ed. from Routledge includes substantial epilogue by Siobhan O’Flynn — Hutcheon’s Theory has defined Adaptation succinctly as “its own palimpsestic thing” that is

an acknowledged transposition of a recognizable other work or works

a creating and an interpretive act of appropriation/salvaging

an extended intertextual engagement with the adapted work. — Hutcheon 8-9

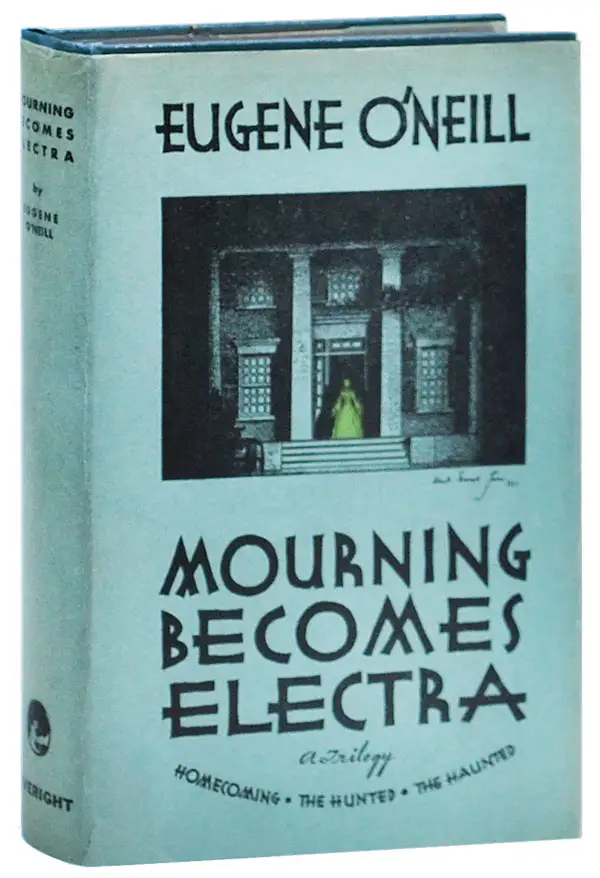

Applying this theoretical model to the adaptation of classical mythology can allow for analytical differentiation between archetypally similar narratives and actually connected intertexts that are aligned by an artist some intentional purpose. Archetypes allow for comparisons, say, of Paul Bunyan and Heracles, who are both viewable as that Campbellian hero of a thousand faces. Conversely, Adaptation, by Hutcheon’s limited definition, relies upon internal Acknowledgement to encourage the reader/viewer to connect the intertexts the artist has in mind, i.e. to read Lavinia and Christine Mannon as characters in a post-bellum oresteia. Eugene O’Neill’s Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), of course, reads as an adaptation of the classical Orestes myth because the playwright wrote it so, acknowledging the source myth in an extended, interpretive transposition to the American stage.

Hutcheon lays down defensible groundrules for defining Adaptation. These rules allow for analysis that can be built upon substantial principles and not upon the occasional observation a clever reader may infer. In Hutcheon’s theoretical realm, the artist controls the narrative and tells the beholder to watch for intertextual connections. She calls this process Acknowledgement because it renders the reader into a state of Knowing. Thus, I can know that Hamlet is thinking Hecuba in the context of Gertrude’s shabby bereavement when he asks the Player to recite “Aeneas’ tale to Dido”. When Shakespeare’s Player extols Hecuba’s abject mourning for her regal spouse, Hamlet’s call for the speech shows the viewer something his psychological state. Shakespeare adapts the Hecuba myth intentionally. And thanks to Hutcheon’s guidance, analysis of the adapation can proceed productively.

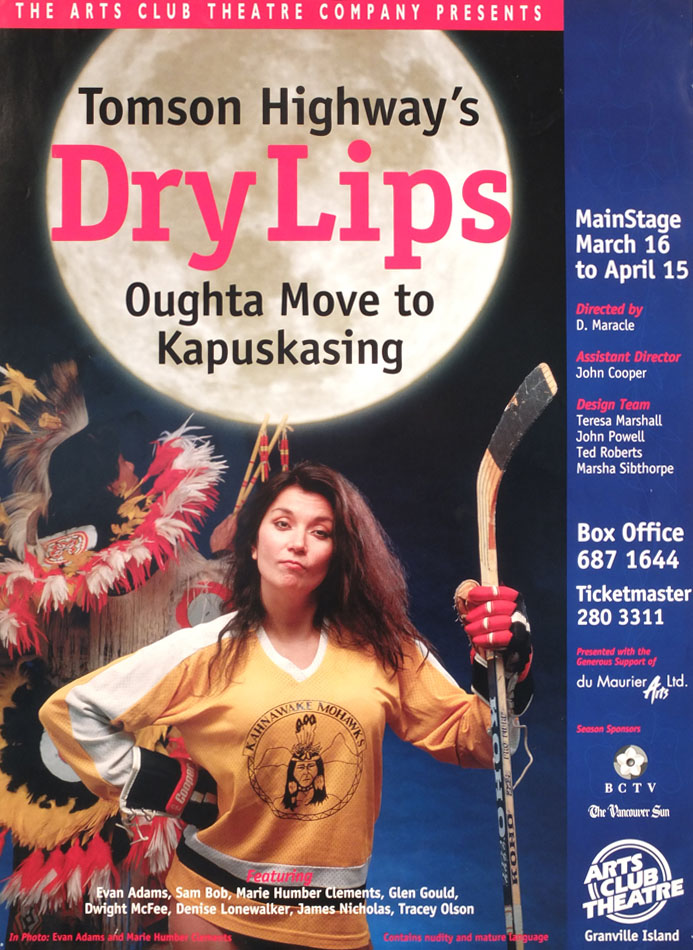

Hutcheon’s late chapter on “Where? When? [contexts for adaptations]” is momentarily problematic for me. She seems at one point to cut a corner, or step out of the fairway and into the weeds, if only for a moment. I criticize a portion of her paragraph on page 149, in which she casually identifies the play Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing (1987) as an adaptation of classical myths of Aphrodite and Athena, if not also of Cybele (i.e. the Pregnant Earth Mother; note Hutcheon’s capitalization). I stumble in Hutcheon’s suggestion that the Aphrodite myth, or the others, is acknowledged by the playwright and that Dry Lips is an adaptation. By her own guidelines, there should be a moment of acknowledgement within the text of the play or within paratextual

commentary by the playwright. When I read the play, I find none.

Tomson Highway wrote Dry Lips Oughta Move to Kapuskasing as part of a vanguard of Native Canadian First-Nation dramatists inclined to bring to the national stage post-colonial voices articulating native experiences and native stories. (Highway is depicted in the Featured Image at the head of this blogpost.) The play premiered in Toronto in 1989 in a production of Native Earth Performing Arts Inc. In its published form, the play holds the important, final anchor in an anthology of Modern Canadian Plays, ed. by J. Wasserman (Vancouver: Talonbooks, 1994), where a few preliminary pages of contextualization clarify the role of the play’s principal character, Nanabush. Having no prior familiarity with Nanabush, the Trickster divinity in Ojibway religion, I met her first in Highway’s introduction. Nanabush is the first speaking character in the play and the central agent driving the action forward on the stage. Nanabush, who is identified in the dramatis personae as “Nanabush ([portraying] the spirit of Gazelle Nataways, Patsy Pegahmagahbow and Black Lady Halked)”, was played in the premier by a single Canadian actress Doris Linklatter. During the play’s action, Nanabush assumes various impersonations and performs her dramatic activities on three different zones of a multi-level stage. Highway states in a prologue annotation that “Some say that Nanabush left this continent when the white man came. We believe she/he is still here among us — albeit a little worse for wear and tear — having assumed other guises. Without the continued presence of this extraordinary figure, the core of Indian culture would be gone forever.” (Wasserman, 322) So the play moves forward because Nanabush makes it so.

Hutcheon introduced me to Highway’s amusing drama, but only with enough detail for her to observe that “In North American stage productions of Dry Lips … one actor plays a trinity of female goddesses (Aphrodite, Pregnant Earth Mother, and Athena) in an echo of Christian imagery; in contrast, when the play was transculturated to polytheistic Japan, three women were used …”. (Hutcheon, 149) As I grapple generally with modern adaptations of classical mythology, a statement like this from a scholar like Hutcheon grabs my interest quickly. But as I have explored the play on my own, I resist increasingly Hutcheon’s corner-cutting in her equation of Highway’s Nanabush with these three major classical goddesses. As it turns out, within Highway’s play, much stagecraft is afoot. And surely Nanabush-Gazelle/Patsy/Black Lady manifests elements of the sexy, ingenious, prodigiously fecund Ewig Weibliche entity. But I see in Highway’s apparatus no acknowledgement that he associates these aspects of the divine Nanabush with goddesses of the Olympian pantheon. Dry Lips’ trickster steals the show. But in the end, the multi-faced female presence in the play emerges for me a powerful First-Nation native essence and not a personage derived from Greek myths.

Hutcheon’s reading of Highway’s narrative seems to me at present more like a reception and less like an adaptation. This is because the playwright’s acknowledgement does not align with Hutcheon’s groundrules as stated above.

So, contrary to my eager anticipation, when I went looking for Dry Lips Ought Move to Kapuskasing and read it, I did not find an adaptation of Aphrodite’s mythology, nor of Athena’s. The goddesses per se do not connect mythologically-intertextually to Highway’s play. I will warrant that Zachary’s “real” wife (358) enters the play in the final minute, a newly delivered mother named Hera Keechigeesik speaking Cree and laughing like Nanabush/Gazelle did in the opening scene.

Future engagement with this interesting play should require me to probe the connection Highway himself may have contrived between the great goddess Hera (qua Earth Mother) and the bawdy young woman who has borne Zachary’s child. Hera Keechigeesik may be the point of acknowledgment upon which Highway hinges an adaption of classical mythology in his Native American dramtic intrigue of Dry Lips Oughta Come to Kapuskasing. Til then, it nags at me that Hutcheon — and not Highway — supplies the connections to Greek mythology, connections the artist himself appears not to have drawn.

Hera2.0100_Highway (perhaps)

— RTM