The protagonist of Cold Mountain, Ada, reads to Ruby’s kids and to her own nine-year old daughter the story of Baucis and Philemon, a myth of gained paradise. Without any overt acknowledgement of this myth’s approach within the novel, Frazier uses the myth’s telling as the very final action of the novel. After the myth is read into the record, no further action transpires.

In the book’s final two paragraphs, Frazier learnedly inserts the reference to Baucis and Philemon while omitting in a periphrasis nearly all details of the referent. Indeed, he glosses over the actual telling of the classical myth.

Ada took a book from her apron and tipped it toward the firelight and read. Baucis and Philemon. She turned the pages with slight difficulty because she had lost the end of her right index finger four years previous on the day after winter solstice. She had been up on the ridge alone cutting trees in the spot where she had marked the sun setting the day before from the porch. The log chain had kinked, and she had been trying to work loose the disordered links when the horse started forward in the traces and pinched off the fingertip clean as snapping a tomato sucker. Ruby poulticed it, and though it took the better part of a year, it healed so neatly you would think that was the way the ends of people’s fingers were meant to look.

When Ada reached the story’s conclusion, and the old lovers after long years together in peace and harmony had turned into oak and linden, it was full dark. The night was growing cool, and Ada put the book away. … — Frazier, Cold Mountain, 448-49

The myth of Baucis and Philemon — arguably the only happy-ending metamorphosis in Ovid’s multivalent Metamorphoses — is applied with remarkable artistry on the last page of Cold Mountain. For the novel overtly adapts the myth of Penelope and Odysseus from its third page right the way through to its epilogue. Homer, Homeric motifs, the study of Greek, thematic comparanda between Inman’s odyssey and Odysseus’ delayed nostos all run throughout the novel. Only a reader with no familiarity of Homer’s Odyssey can miss how “Cold Mountain asserts itself as an authentic American Odyssey”, as the dustjacket claims. Yet, Baucis and Philemon comes at us not from the Homeric narrative but from out of the blue, entirely unmentioned to this point within Cold Mountain.

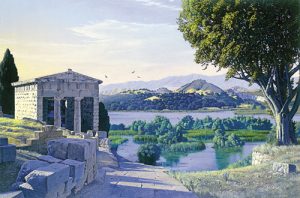

Frazier’s application may achieve the same multivalance as Ovid in the Metamorphoses, where a humble aging couple, Baucis and her husband Philemon, graciously receive the gods Mercury and Jupiter then receive in turn the gift of metamorphosis from human into intertwined trees — a linden and an oak — which shadow the temple of Jupiter in the spot where they once had lived. Ovid summarizes with the moral that “gods love gods and care for those who honor them.” Like Baucis and Philemon within the Ovidian myth and Ada seems to express within the epilogue of Cold Mountain a yearning to achieve everlasting (not actually immortal nor eternal) intertwining and natural repose.

Spoiler alert: the next paragraph includes details that might spoil one’s first reading of Cold Mountain.

The consummation of Inman’s nostos and Ada’s occurs over about a dozen pages and several scenes within the novel’s final forty pages. There is love-making and detailed intimate planning about the future between Ada and Inman who come to know much about one another’s past that they never could have known before. They talk about growing old together. (434) Frazier thematically intertwines the two lovers in their union, e.g. “Ada and Inman lay woven together on their bed.” (430). Elsewhere they are “intertwined” and talking in bed. (435) As Ovid involved several words with the intertwining letter “X” in the metamorphosis of Baucis and Philemon (Met. 8.718-19), Frazier follows suit. Interspersed among all that intertwining Fazier weaves a fascinating negotiation between Ada and Ruby, who at one point speaks her mind with customary clarity: “… I’ll just say out plain what’s on my mind. It’s that we can do without him. You might think we can’t, but we can.” (409)

Ada’s character development within the novel is complete in that gloss slipped into the place of the Baucis and Philemon myth. She who entered the novel as a mere girl from Charleston has become a self-sufficient pioneer with the moxy now to mark solstices, clear trees, team a workhorse, and survive an involuntary amputation. Through the novel’s nearly 450 pages, Ada progresses from a girl dressed in chiffon and trained too closely in classical literature and has become this capable woman. Readers of the novel will note how fitting is the detail that Ruby so effectively poulticed the wound. And they will note how very much like Ruby Ada herself has become. Indeed, the narrative has proved that Ruby and Ada together can do without Inman. And in this light that final intertwining of two lovers “after long years” must be the remarkable joining of Ada and Ruby.

Linda Hutcheon’s Theory of Adaptation calls for adaptations to be “extended intertextual engagement[s] with the adapted work”. (8) Because the myth of Baucis and Philemon receives far less than extended engagement within Cold Mountain, we are best able to conclude with applying the mythological adaptation only to the novel’s formal “Epilogue: October of 1874”, pages 446-49, rather than to the whole novel. There Homer’s Odyssey receives extended adaptation. The reference to Baucis and Philemon does not formally qualify Cold Mountain as an adaptation of the myth. For, the myth is not sustained across the novel. That sort of adaptation certainly applies to the novel’s adaptations of Ada as Penelope and Inman as Odysseus. I shall argue elsewhere that reading Ruby’s development within the novel as an Athena adaptation is a thoroughly sustainable. I would like to believe, though, that that argument needs to transpire in a venue where there is more time and space for appropriate development.

I would assign to the novel the OGCMA index Penelope2.0011_Frazier or OdysseusReturn2.0011, preferring the former because of the novelist’s more surprising development of Ada’s character.

_____ Roger T. Macfarlane

Charles Frazier (1997), Cold Mountain: a novel (New York: Vintage Books) — winner of the National Book Award.

The New York Times Book Review noted that “he has reset much of the Odyssey in 19th-century America, near the end of the Civil War.”

Linda Hutcheon (2013), A Theory of Adaptation, 2nd ed. (London and New York: Routledge), 8-9.

see Emily A. McDermott (2004), “Frazier Polymetis: Cold Mountain and the Odyssey” Classical and Modern Literature 24.2: 101-24. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/classics_faculty_pubs/5

This is a very useful article featuring salient observation, backed by careful documentation.

“The most extensive, systematic and thematically significant intertextuality between Cold Mountain and the Odyssey occurs in the characterization of Inman, in the portrayal of his relationship with Ada and in the reunion of the two at end of the novel.”

—— McDermott’s article is downright good, to be sure, but I would argue that the characterization of Ruby as Athena, especially in her enhanced adaptation as Ada/Penelope’s formative helpmeet is even more compelling and more systematically significant than Inman’s as Odysseus.