Agnolo Bronzino executed in 1539 a commission and painted Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, arguably Europe’s most eligible bachelor. The cocksure portrait (vid. left; link) was intended to convince Eleanora of Toledo of the desirability of her becoming a new Eurydice to Cosimo’s Orpheus. The viewer was supposed to be inspired to marriage with the most heroic lover of all time. Cosimo:Orpheus::Eleanora:Eurydice. Bonzino captures Cosimo in a moment of musical enchantment. Garbed — well, heroically nude — as Orpheus, the Florentine magnate charms Cerberus on the viol da gamba. Seated on a rock at the gates of hell, Cosimo is fiddling. He’s busy making history on this epic rescue mission. But, Cosimo qua Orpheus takes this intimate moment to pause and look back over his left shoulder at the viewer as if it sing something lyrical, something seductive to Eleanora. That something in our contemporary vernacular might sound something like this — “I’d be the voice that urged Orpheus, when her body was found… Imagine being loved by me! I won’t deny I’ve got in my mind now all the things I would do…”

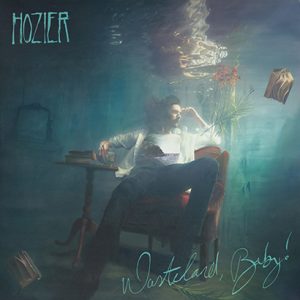

That something just quoted is part of the lyric seduction driving the song “Talk” as recorded by Hozier, the Irish blues artist (b. Andrew John Hozier-Byrne), on his album Wasteland, Baby! (2019, Rubyworks Records). Hozier’s rhetorical objective seems hardly different from Cosimo’s purpose (projected through Bronzino).

To judge by the candid reactions to “Talk” offered on the song’s YouTube page, Hozier’s Orphic adaptation strikes just the right chord indeed: listeners express visceral erotic reactions to Hozier’s invitation to “Imagine being loved by me.” “Let’s get real here for a sec.,” says Elénore, “This is 10000% a strip-tease song.” And several others echo Elénore (coincidental irony, viz. Eleanora of Toledo, noted) sentiment. Few of the respondents address the mythological adaptation; most perceive the driving sex of the singer’s promises. Another respondent (Emily Little) states, “Imagine being the person he writes these songs about.”

In full, Hozier’s lyric in “Talk” builds twice to the invitation to “imagine being loved by me” and expresses three times in refrain his desire to seduce the beloved. Rhetorical refinement is going to be critical, he says, to keep the beloved from “find[ing] out how I’m imaginin’ you.”

I’d be the voice that urged Orpheus

When her body was found (Hey ya)

I’d be the choiceless hope in grief

That drove him underground (Hey ya)

I’d be the dreadful need in the devotee

That made him turn around (Hey ya)

And I’d be the immediate forgiveness

In Eurydice

Imagine being loved by me!

I won’t deny I’ve got in my mind now all the things I would do

So I’ll try to talk refined for fear that you find out how I’m imaginin’ you.

I’d be the last shred of truth

In the lost myth of true love (Hey ya)

I’d be the sweet feeling of release

Mankind now dreams of (Hey ya)

That’s found in the last witness

Before the wave hits

Marvelling at God (Hey ya)

Before he feels alone

One final time

And marries the sea

Imagine being loved by me

I won’t deny I’ve got in my mind now all the things I would do

So I’ll try to talk refined for fear that you find out how I’m imaginin’ you.

I won’t deny I’ve got in my mind now all the things we could do

So I’ll try to talk refined for fear that you find out how I’m imaginin’ you.

A couple of guitars, a simple rhythm box and a couple of background vocalists help set the mood for Hozier’s seduction. Not to deny the musical accompaniment, but it’s the voice. Hozier’s bluesy persuasion harbors no urgency as he goes about his business, this seduction. Thus, the first verse proceeds with a four-part approach to the Orphic dilemma. The mythological scheme would look something like this:

- Orpheus was urged by some (inner?) voice to respond to his lover’s death; I would be the one to prompt that response, if you let me love you.

- Orpheus was driven inexorably by grief to the Underworld with no hope of success; I would be the one to insist he still must venture, if you let me love you.

- Orpheus’ needy devotion to his beloved compelled his retrospection; I would embody that needy devotion, if you let me love you.

- Eurydice, understanding her lover’s intention, forgave him immediately; I would inspire such reactions from you, if you let me love you.

While the voice and promises Hozier adapts in this song belong clearly to the tradition of the Orpheus & Eurydice myth, the adaptation seems especially biased toward the Ovidian variants rather than the Vergilian. It was Ovid who allowed the narrator to comment upon Eurydice’s silence in the moment of her second death “what she might have to complain about, except that she was loved!” (Ov. Met. 10.61) Hozier reiterates or reinvents Ovid’s Eurydice’s “immediate forgiveness” which anciently corrected Vergil’s Eurydice (Ver. G. 4.494-98), but her tacit forgiveness pertains through until Hozier’s adaptation gives it new voice in 2019.

——— Roger T. Macfarlane

with thanks to Braxton Johanson for the lead

What I know about Bronzino’s “Cosimo as Orpheus” portrait I attribute to Janet Cox-Rearick (2002) in The Medici, Michelangelo, and the Art of Late Renaissance Florence (New Haven and London: Yale UP and Detroit Institute of Arts), 153-54; and from R.B. Simon, “Bronzino’s Cosimo I de’ Medici as Orpheus,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 81 (1985) 16 – 27.