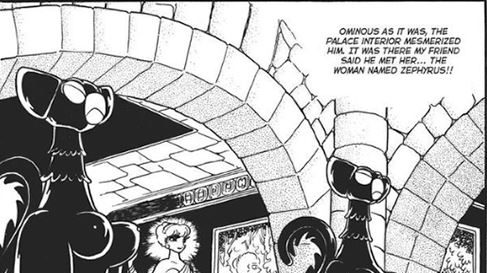

The work called “Perseus and Andromeda — a role reversal” reworks the central premise of the familiar moment in the Perseus and Andromeda rescue. Here two nudes participate heroically in the rescue of a victim on a sea-side cliff. A desiccated piscine seamonster rises between the two human figures. Perseus is recognizable only by the context, a helpless nude chained to a cliff. Perseus’ head is substituted symbolically in surrealist fashion by a meaningful fishhead. On this, more below. In the artwork, Perseus’ unheroic nudity leaves him utterly exposed to the just-now thwarted assault of that marine creature whose viability in this precise moment is somewhat indeterminate; but, if not petrified in the sea, the enormous fish is unlikely to pose a threat any longer to the naked man in distress. Most viewers’ eyes, I dare say, pay less attention to that fish than to the striking arrival of this work’s most surprising figure, a virtually heroic Andromeda entering the scene from the left. She is not entirely nude, for she carries a shield on her arm, a helmet on her head, and talaria on her feet.

Christina Neofotistos, who created this adaptation of the Andromeda myth is a digital graphic artist whose work is known to me in only nine pieces. Although I have attempted to contact the artist directly, I am left with only sparse pieces of biographical information — a) that she is a transgender female Greek artist, and b) that she demures her claim to artistry in the statement “I don’t know what art is, so i don’t know if i am an artist.” These are exhibited on a virtual online gallery at zazie.at, where the artist is named Jade Christina Green. The digital pictures are variously signed with a monogram that seems to comprise the letters C, N, and Φ (Greek Phi). The watermark on the Zazie gallery’s images connects the works attributed to “Jade Christina Green” to “copyright 2002 by Cneofotistos”. If, as I surmise, Neofotistos’ name is an aptly contrived professional moniker, it indicates the artist’s emphasis on novelty, her attention to “new light” (neo-phot-ism?).

Classic portrayals of Andromeda and her descendants — from Angelica’s rescue by Roger to Jaws’ first victim, an unrescued skinny-dipper eaten by a huge shark — equate the girl’s vulnerability to her erotic charge. Surely Cepheus and Cassiopeia did not need to strip their daughter naked before chaining her to that rock as bait for the ravaging sea monster. Doing so merely added insult to her injury. But painters right the way through from Titian to Witwael and beyond follow suit. Not Neofotistos! In this Andromeda scene, the artist portrays Andromeda utterly in the altogether, in surprising heroic nudity that completes the image. For, Neofotistos arms her feminist hero with a drawn and remarkably erect shining sword which she directs from her loins at the languid Perseus, indeed directly at his loins. Whether Neofotistos has purposefully chosen to subvert classical insistence — because, classically, the hero in this moment wields the curved harpe, not just some straight, old sword — is a matter of intrigue. Andromeda holds her erect sword, though, with her left hand as it surges like acquired genitalia and follows her gaze toward Perseus on the rock.

The reversal of roles in this picture is overt. Copyrighted in 2002 and published on Zazie.at (http://www.zazie.at/SpecialEditions/index.htm) in 2004, it predates another feminist rethinking of the Perseus myth, the infamous “Medusa with the Head of Perseus” (2008) by Luciano Garbati. (Medusa2.0100_Garbati) Neofotistos’ emphasis on reversal may explain the divergence from Ovid’s dogged insistance on putting Perseus’ shield on his left arm, because here the role-reversed Andromeda carries her shield on her right.

Neofotistos’ overt emphasis on those fulsome gull-like sets of wings that propel her nude Andromeda forward to Perseus’ rescue remind me of Titian’s foregrounding of Perseus’ talaria, where the painter

seems overtly to insist that this hero travels not on a winged horse, but rather in the mode that Ovid meticulously foregrounds in his ur-narrative.

I first met this remarkable Andromeda narrative in a learned article, where a single sentence subjects the arriving heroine to interpretation within the framework of Perseus. “This tradition [sc. of male power rescuing the exposed female] was questioned and subverted in a graphic by the Greek digital artist Christina Neofotistou (2002), in which the phallic P[erseus] role is given to a female figure and the erotic Andromeda role to a male.” (Mergenthaler*) The cynic will ask why Andromeda so rarely merits a separate article of her very own; and the optimist will hope that subsequent editions of such works as the Reception of Myth and Mythology will feature Andromeda and her peers in articles of their own, rather than secondary figures in the articles titled after their rescuers. Neofotistos’ contribution may effect such a change.

“Perseus and Andromeda — a role reversal” is one of nine works exhibited in zazie.at’s special exhibition gallery by Jade Christina Green (a.k.a. Christina Neofotistos). While all nine artworks exhibited there share a surrealist element to larger or less degree, three work as adaptations of particularly classical mythology. The portrait of Salvador Dali subdues classical forms but is unmistakably referential to the togate Dali who selflessly gives the fingers of his left hand to a foregrounded cheese grater. Christian symbolism is even more provocatively in play in “The Virgin Mary Diagnoses a Case of Thalassemia β”, or in the erotically super-charged labial apple of “Eve”. One seems to know something of the artist’s autobiographical background from these reversals of religious iconography; “Oppressed Childhood” and “Fellatio, or Fish Planted in a Bowl of Water,” are perhaps less revelatory.

Three of the nine works in the gallery include, beyond, the Andromeda, also the mythologically forward “Bacchus delirius, or the masturbational social hierarchy” and “Trojan Horse”. The latter graphically plays on our contemporary term for voyeuristic cyberaggression, the malware that enters a personal computer via pornographic seduction to impregnate the victim’s privacy as if with marauding assailants. That bloody key which exits (?) the genitals of Neofotistos’ lithe temptrix — or the staircase in her thigh, or the barren landscape behind her — probably signals as clearly to Dali-aware surrealists as the picture’s overt adaptation symbolizes for classicists a neo-Vergilian breech of Troy, a city that is porno vinoque sepulta.

Among the gallery’s items directly involved in the interpretation of Neofotistos’ “Perseus and Andromeda” are the three works using fish to represent phallo-centrist energy. From among the fish in Neofotistos’ Zazie gallery, comes an interpretive symbol to explain why she gives her Perseus bound a fishhead rather than human head atop his splendid male body. The “fish planted in [its] bowl” in “Fellatio” is a non-descript grey-scaled fish rising from shining red lubriciousness that would seem altogether fluid and inviting were it not for the tidy fisherman’s knot attaching this enticement to an unseen angler’s rod and creel. A similar fish in “Eve” rises from the glassy surface of still water to gaze at or enter the labial provocation of an overtly anatomical apple — a single piscine admirer versus one enticing fruit aptly proportioned to receive him. The most obvious — to my mind — interpretation of Neofostitos’ piscine phallocentrism rises in “The Folly of Formal Dress Code”, where a hooked fish is a metamorphosed necktie, its tail tied in a neat Windsor knot around the collar of a formal evening suit on a haberdasher’s mannequin. Formal, patriarchal sartorial “folly” becomes lethal in the symbolic hooking of this caught fish. His brethren appear in more sexualized environments among Neofotistos’ gallery. Her substitution of Perseus’ humanoid head by the head of a grey fish, which is contrived to resemble the male glans, renders the customary hero of this mythological moment is nothing but flaccidity; Andromeda, conversely, is nothing but sexual energy. Perseus’ rescue is only to be effected by the arrival of the most winsome heroine Neofotistos seems capable of conjuring into pixels.

Roger T. Macfarlane — macfarlane@byu.edu

_____

* Volker Mergenthaler (2010), s.v. “Perseus” in Reception of Myth and Mythology ed. by M. Moog-Grünewald, Brills’ New Pauly Supplements 1.4 Leiden and Boston), 521.